More than 80% of our oceans are unmapped, unobserved and unexplored. When researchers probe these deep mysterious waters, something new and exciting often lurks in the dark, waiting to be discovered…

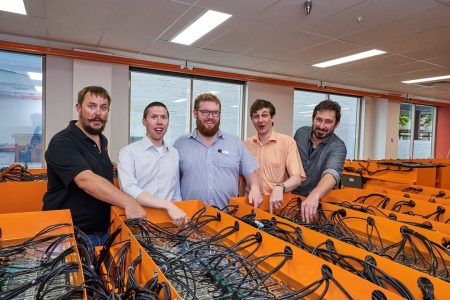

This time, a team of scientists from Newcastle University dipped their ultra-deep ‘lander’ systems into the deepest location on Earth, the Mariana Trench, for their deep-sea exploration studies.

But when they retrieved it, they encountered something horrifying…

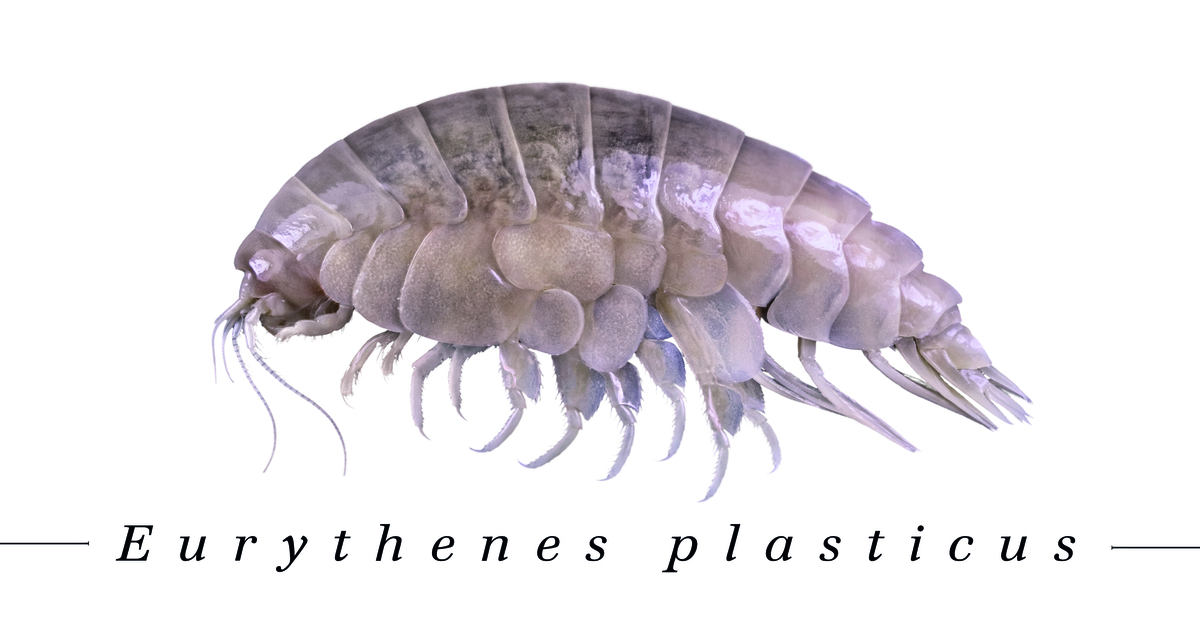

The collection chambers of their lander system teemed with amphipods (scavenger relatives of crabs and prawns that thrive in the deep abyss), with plastic filling up their tiny bodies.

Microplastics in the deep ocean.

Initially planning to study how the deep-sea creatures differ from one remote trench to another, Dr Alan Jamieson, lead researcher of the project and senior lecturer in Marine Ecology at Newcastle University, stumbled upon this discovery by pure chance.

And almost on a whim, he devoted most of his time to analysing the amphipods for toxic, human-made pollutants.

The research team found plastics galore. They identified plastic fibres and fragments – made of polyethylene terephthalate (PET), a type of plastic broadly used in plastic bottles and packaging – in 72 per cent of the amphipods collected, from all six trenches surveyed.

In the least polluted trench, half of the amphipods had at least one fragment of plastic in them. At almost 11 kilometres deep, the lowest point in any ocean, all the amphipods had plastic in their gut.

They published their initial findings in the journal Royal Society Open Science, which eventually led to the classification of the animal as an entirely new species – Eurythenes Plasticus. The name was also given as a statement to highlight how severe our microplastic problem has become.

Alarming consequences to the whole deep-sea ecosystem.

Stuck to the microplastics in the tiny creatures were also persistent organic pollutants (POP) such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs).

PCBs are hydrophobic chemicals, which essentially means they’ll bind to anything else but water. And to make things worse, plastics are almost like a magnet to these toxic chemicals. Microplastics collect these toxins, turning the fibres into sinks for other contaminants. They ultimately sink into the deep sea, where creatures mistake them as food.

These nasty chemicals, which have been banned for decades but persist in nature for much longer, were found in some amphipods at levels 50 times higher in concentration than those seen in crabs from a highly polluted river in China.

These toxins have devastating effects on the organism’s digestive system and reproductive health. Their chances of survival, as a result, would be gravely affected, which in turn alters the whole food chain in the deep-sea ecosystem.

Putting the spotlight on microplastics.

Most of the world is still (blissfully) unaware of just how widespread the problem of plastic pollution is today.

Microplastics, which simply cannot be fished out of the waters like bulky plastics, pose even greater threats to humanity and the environment.

The flood of plastic does not stop at country borders. Nor does it stop at borders separating land and sea. And the deep-sea is anything but free from the consequences of what happens above it.

Perhaps this issue should be given a larger spotlight so that it could be tackled more effectively? After all, plastic in fish is certainly not palatable!