One of the motivations to explore space, visit other planets, and land rovers on Mars is to drive innovation and build the technologies of the future.

Say hello to the “Space Garbage Service” (or as we affectionately call it, the SGS).

Multi-national effort to clean-up space.

Tokyo-headquartered Astroscale, a private satellite removal company, launched Elsa-D (End-of-Life Service by Astroscale demonstration) in March, which consists of a “servicer” that will track down and capture a “client” in complicated space maneuvers. Check out a video on how the duo work here. They are currently working on its successor – the Elsa-M – to de-orbit larger pieces of debris, gradually making space safer for astronauts and satellites.

A space-mining startup in China, Origin Space, just launched a space-robot-cleaner prototype into low-Earth orbit. Capable of scooping up debris left behind by other spacecraft using a giant net and then burning them with its electric propulsion system, the NEO-01 will also peek into deep space to observe small celestial objects.

In 2025, the ESA in partnership with a Swiss start-up called ClearSpace, will embark on a mission, dubbed ClearSpace-1, to remove a challenging 100 kg payload adapter at a low-cost. The robot will secure the space junk with its arms, drag it down into the Earth’s atmosphere, and unlike the previous two efforts, both the spacecraft and the junk will burn up and perish.

Many missions are also carried out back here on Earth, some of which include the development of space-junk-zapping lasers. A collaboration between the Australian National University (ANU), Electro Optic Systems (EOS) and Space Environment Research Centre (SERC), the “guide star laser” can track and move space debris out of orbit to avoid collisions.

The complex constellation of space junk is also constantly tracked and monitored for any collision risks using radio telescopes. For example, astronomers at Curtin University use and process massive amounts of data collected by the telescopes with supercomputers to detect and monitor space junk and satellites in Earth’s orbit. This will greatly improve the accuracy of space junk modelling and predict any unusual activity such as collisions.

A volatile junk-yard in space.

But why has this new industry popped up?

On Earth we generate over 2 billion tonnes of solid waste each year and our propensity for manufacturing garbage is spilling over into space.

A plethora of space activities and events, such as explosions, spacecraft collisions and expendable rocket stages, result in a growing cloud of orbiting debris surrounding Earth.

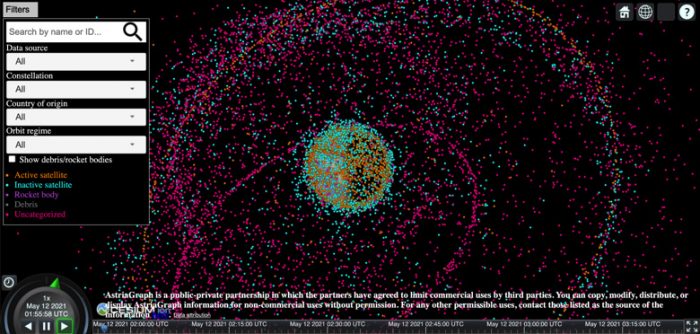

According to NASA, there are more than 25,000 objects larger than a softball, 500,000 bigger than a marble and millions of pieces of tiny junk simply too small to track.

This definitely doesn’t sound like good news.

Zooming by at almost 30,000 km/h, even a tiny piece of space junk can have catastrophic repercussions.

The ESA said a pea-sized fragment can disable critical flight systems on a satellite.

Anything more than 10 cm3 impacting satellites or spacecraft would instantly turn into space rubble.

AstriaGraph, an open access tool to visualise resident space objects, developed by Moriba Jah at the University of Texas at Austin. The map revealed more than 200 potential “super spreader” events.

Ticking time bombs in space.

Growing concerns are placed on super-spreader events, where satellites or rocket bodies that have been up there for decades, like ticking time bombs, might explode or get hit by another object.

In 2009, an Iridium satellite collided with a derelict Russian satellite due to inadequate tracking of both objects.

Once disintegrated into thousands of smaller pieces, this junk will pose much higher threats to some 3,500 (and rapidly growing) working satellites orbiting Earth.

Position, navigation, timing, financial transactions, climate warnings – satellites that provide these critical services could at any point get hit by these pieces of debris and stop functioning, grinding some activities to a halt.

With more and more countries having the ability to launch rockets into space, global governments and spaceflight companies must recognise the inherent responsibility to ensure that space is kept clear for what really matters – exploration, not accumulation.