For more than half a century, the Arecibo Observatory (affectionately called Arecibo in this article) in Puerto Rico was the largest single-dish telescope on Earth.

Initially designed for atmospheric scientists to study Earth’s ionosphere, over the years the facility blossomed into one of the most iconic trailblazers in the fields of planetary science and radio astronomy.

And since then, the observatory has been a source of countless astronomical breakthroughs. From discovering the first-ever binary pulsar — a study that tested Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity and earned its researchers a Nobel Prize in 1993 — to spotting the first planet outside our Solar System and mapping the surface of Venus and Mercury, Arecibo has been a gift that keeps on giving.

Even current space endeavours such as NASA’s asteroid-hunting mission, DART, and its asteroid-sampling mission, OSIRIS-REx, owe their success partly to the sea of data collected from observations made by Arecibo in the past five decades.

Did you know that Arecibo was something of a pop culture icon too? It enjoyed a star-studded career as a backdrop for scenes in the James Bond film, Goldeneye (picture on the left), and the Jodie Foster Sci-Fi epic, Contact.

So when Arecibo dramatically collapsed in 2020 due to cable failures, the news sent many in the scientific community into mourning. But despite this tragedy, Arecibo’s legacy lives on, and so does its data.

Understanding how galaxies develop.

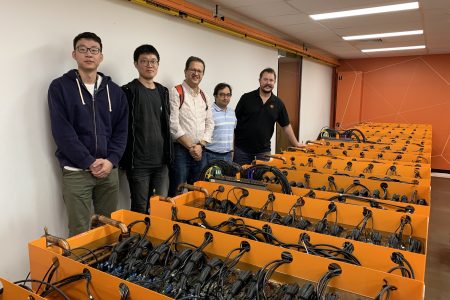

Some of that data is being used by astronomers from the University of Western Australia (UWA) and the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research (ICRAR) in Perth.

UWA and ICRAR scientists aim to better understand how our local neighbourhood of galaxies evolved and formed, including our galaxy, the Milky Way. They have been rigorously testing the “Fall relation” — a theory that suggests the mass of stars belonging to a galaxy and its rotation directly correlate to each other and dictate how a galaxy will grow and evolve.

A study led by PhD candidate Jennifer Hardwick has already yielded impressive results. Published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Arecibo data collected from 564 galaxies of varying shapes and ages represents the largest sample set of its kind ever. Her work has challenged astronomers’ current understanding of how galaxies change over time, while providing a constraint for future researchers to develop these theories further.

What’s momentous about Hardwick’s results is that they contradict previous knowledge concerning the relationship between the mass of stars and a galaxy’s rotation. Furthermore, her study also provides one of the best measurements of the connection between angular momentum and other galaxy properties in the local Universe, which have been lacking in the past due to the difficulty in measuring angular momentum.

Highlighting the importance of revisiting past research.

These findings are testament to the need to revisit past research as technology advances, in an effort to ensure that the critical scientific foundations that underpin new scientific discoveries are on solid ground.

Fortunately, the mountain of telescope data — three petabytes or 3,000 terabytes, to be exact — from Arecibo has been securely backed up off-site and transferred to the Texas Advanced Computing Center’s (TACC) Ranch archival storage system. This data includes information from thousands of observing sessions, equivalent to watching around 120 years of high-definition videos. Furthermore, the data is also made accessible to astronomers all across the globe, who will use it to continue Aceribo’s legacy of discovery and innovation for decades to come.

Marrying the data-crunching ability of today’s massive supercomputers with the advanced machine learning tools and software available, Aricebo’s data can open the door to even more discoveries about the heavens above.

And with upcoming exciting science experiments using state-of-the-art space and radio telescopes such as the James Webb Space Telescope and the Square Kilometre Array, astronomers will continue unfolding the mysteries of the Universe, one observation at a time.